|

|---|

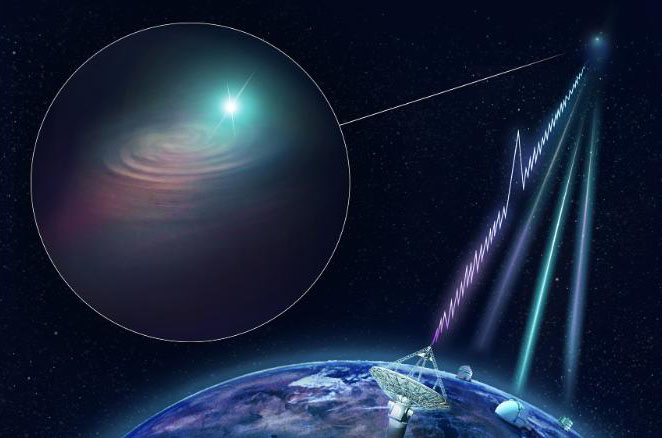

| An artist's impression of CSIRO's Australian SKA Pathfinder radio telescope finding a fast radio burst and determining it's precise location. |

|

A mysterious fast radio burst was traced to a galaxy 3.6 billion light-years away

CNN

Sat June 29, 2019

For the first time, a single burst of cosmic radio waves has been traced to its point of origin: in this case, a galaxy about 3.6 billion light-years from Earth.

These radio bursts are only millisecond-long radio flashes, and such rapid bursts themselves aren't rare in space. But finding out where they came from is incredibly difficult.

People love to believe that they're from an advanced extraterrestrial civilization, and this hypothesis hasn't been ruled out entirely by researchers at Breakthrough Listen, a scientific research program dedicated to finding evidence of intelligent life in the universe.

Astronomers were able to pin down the source of a repeating fast radio burst in 2017. But single radio bursts are harder to pinpoint because they don't reoccur.

The single radio burst, dubbed FRB 180924, was discovered by the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder radio telescope, or ASKAP, in Western Australia.

Three of the largest telescopes around the world -- Keck, Gemini South and the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope -- were able to image the burst. The findings of this observation were published Thursday in the journal Science.

Fast radio bursts, often referred to as FRBs, were first discovered by astronomers in 2007. The quest to discover more radio bursts since then has uncovered 85, including a couple that repeat from the same location.

"This is the big breakthrough that the field has been waiting for since astronomers discovered fast radio bursts," said Keith Bannister, lead study author and principal research engineer at CSIRO, Australia's national science agency.

Because the bursts are so short and hard to track, Bannister's team found a way to freeze and save data collected by the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder in a fraction of a second after the telescope detects a burst.

Data from the detection was used to create a map showing the point of origin. The burst came from a galaxy about the size of our own, 3.6 billion light-years away. It's on the outskirts of that galaxy.

"If we were to stand on the Moon and look down at the Earth with this precision, we would be able to tell not only which city the burst came from, but which postcode -- and even which city block," Bannister said.

"We identified the burst's home galaxy and even its exact starting point, 13,000 light-years out from the galaxy's centre in the galactic suburbs," Adam Deller, an author of the study and an associate professor at the Swinburne University of Technology's Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, said in a statement.

Compared with the origin point of the repeating fast radio burst detected in 2017, this single source origin is very different.

The repeating burst came from a small galaxy full of forming stars. The single burst came from a massive galaxy that has low rates of star formation.

"This suggests that fast radio bursts can be produced in a variety of environments, or that seemingly one-off bursts detected so far by ASKAP are generated by a different mechanism to the repeater," Deller said.

Of course, the biggest mystery of fast radio bursts in space endures: Why do they happen? But knowing where they come from is a giant step in the right direction of understanding them.

The bursts can act like a signature for decoding the space between star systems.

"These bursts are altered by the matter they encounter in space," said Jean-Pierre Macquart, study author and associate professor at the Curtin Institute for Radio Astronomy., in a statement "Now we can pinpoint where they come from, we can use them to measure the amount of matter in intergalactic space."

Share your thoughts in the Forum

Share your thoughts in the Forum